The latest national health survey has confirmed a grim prediction of the country’s smoking problem: that tobacco use among Indonesian teenagers is on the rise, while there is little sign, if any, that the trend could be reversed in the near future.

The trend is seen as alarming, with antitobacco activists and health officials warning it could prevent the country from benefiting from its demographic bonus expected to occur in 2030 and achieving its Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

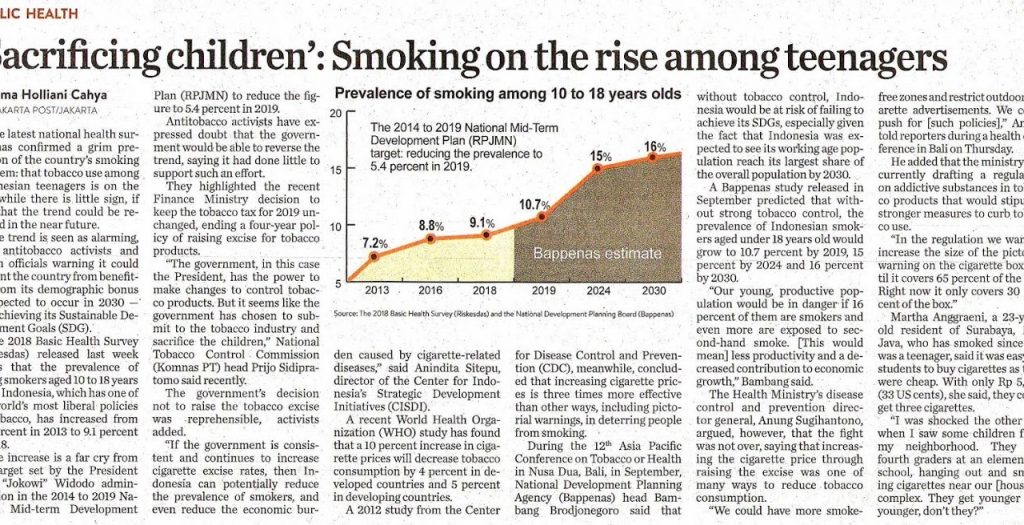

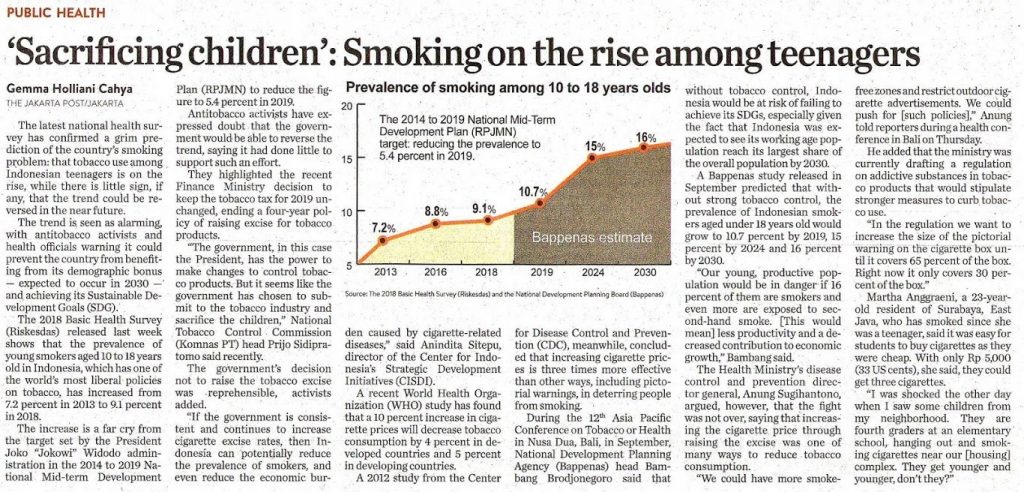

The 2018 Basic Health Survey (Riskesdas) released last week shows that the prevalence of young smokers aged 10 to 18 years old in Indonesia, which has one of the world’s most liberal policies on tobacco, has increased from 7.2 percent in 2013 to 9.1 percent in 2018.

The increase is a far cry from the target set by the President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo administration in the 2014 to 2019 National Mid-term Development Plan (RPJMN) to reduce the figure to 5.4 percent in 2019.

Antitobacco activists have expressed doubt that the government would be able to reverse the trend, saying it had done little to support such an effort.

They highlighted the recent Finance Ministry decision to keep the tobacco tax for 2019 unchanged, ending a four-year policy of raising excise for tobacco products.

“The government, in this case the President, has the power to make changes to control tobacco products. But it seems like the government has chosen to submit to the tobacco industry and sacrifice the children,” National Tobacco Control Commission (Komnas PT) head Prijo Sidipratomo said recently.

The government’s decision not to raise the tobacco excise was reprehensible, activists added.

“If the government is consistent and continues to increase cigarette excise rates, then Indonesia can potentially reduce the prevalence of smokers, and even reduce the economic burden caused by cigarette-related diseases/’ said Anindita Sitepu, director of the Center for Indonesia’s Strategic Development Initiatives (CISDI).

A recent World Health Organization (WHO) study has found that a 10 percent increase in cigarette prices will decrease tobacco consumption by 4 percent in developed countries and 5 percent in developing countries.

A 2012 study from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), meanwhile, concluded that increasing cigarette prices is three times more effective than other ways, including pictorial warnings, in deterring people from smoking.

During the 12th Asia Pacific Conference on Tobacco or Health in Nusa Dua, Bali, in September, National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) head Bambang Brodjonegoro said that without tobacco control, Indonesia would be at risk of failing to achieve its SDGs, especially given the fact that Indonesia was expected to see its working age population reach its largest share of the overall population by 2030.

A Bappenas study released in September predicted that without strong tobacco control, the prevalence of Indonesian smokers aged under 18 years old would grow to 10.7 percent by 2019, 15 percent by 2024 and 16 percent by 2030.

“Our young, productive population would be in danger if 16 percent of them are smokers and even more are exposed to second-hand smoke. [This would mean] less productivity and a decreased contribution to economic growth,” Bambang said.

The Health Ministry’s disease control and prevention director general, Anung Sugihantono, argued, however, that the fight was not over, saying that increasing the cigarette price through raising the excise was one of many ways to reduce tobacco consumption.

“We could have more smoke-

free zones and restrict outdoor cigarette advertisements. We could push for [such policies],” Anung told reporters during a health conference in Bali on Thursday.

He added that the ministry was currently drafting a regulation on addictive substances in tobacco products that would stipulate stronger measures to curb tobacco use.

“In the regulation we want to increase the size of the pictorial warning on the cigarette box until it covers 65 percent of the box. Right now it only covers 30 percent of the box.”

Martha Anggraeni, a 23 year old resident of Surabaya, East Java, who has smoked since she was a teenager, said it was easy for students to buy cigarettes as they were cheap. With only Rp 5,000 (33 US cents), she said, they could get three cigarettes.

“I was shocked the other day when I saw some children from my neighborhood. They are fourth graders at an elementary school, hanging out and smoking cigarettes near our [housing] complex. They get younger and younger, don’t they?”